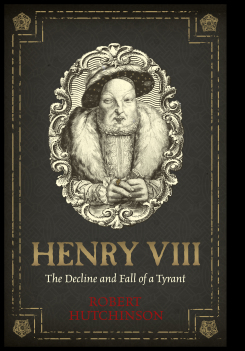

Henry VIII : The Decline and Fall of a Tyrant

Robert Hutchinson

Down the centuries, Henry VIII has sparked powerful passions. Cardinal Reginald Pole, the exile who fought tooth and nail to defend Holy Mother Church, told him: ‘Your butcheries and horrible executions have made England the slaughterhouse of innocence’. As Henry had massacred his kith and kin, one can sympathise.

In the eighteenth-century, the Irish satirist Jonathan Swift scribbled his opinion of the old ogre in the margin of his book: ‘I wish he had been flayed, his skin stuffed and hanged upon a gibbet. His bulky guts and flesh left to be devoured by birds and beasts for a warning to his successors for ever. Amen’. Hardly appropriate sentiments, perhaps, for the Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin.

More than a century afterwards, Charles Dickens, in his Child’s History of England, described Henry ‘as the most intolerable ruffian… with blood on his hands, a disgrace to human nature and a blot of blood and grease’ on the fair face of his realm.

In recent years, England’s most famous monarch has been defined more by his six marriages and sometimes trite television dramas, rather than who he was truly was. A tyrant, yes, reigning over subjects, living in mortal terror of his retribution, as well as a court locked in febrile, dark conspiracy by those jockeying for influence and power.

In his old age, the athletic Renaissance prince had long since withered away. Here is an unfamiliar Henry VIII; a vulnerable, frightened and lonely old man, for whom the sands of time were rapidly dwindling. His massive ego and his dreams of military glory became ever more ill-matched to reality.

It is time to examine what really drove the king in his religious and diplomatic policies; what we would recognise today as the genocide he brutally exacted upon the inhabitants of Scotland and northern France, the bare-faced fraud of his ‘Great Debasement’ of England’s currency, and the reckless borrowing that sent his kingdom crashing into bankruptcy. There were also the assassins he hired to murder the traitors who had fled abroad, like the elegant but ruthless gangster Ludovico da l’Armi.

Since I published Last Days of Henry VIII in 2005, there has been remarkable progress in understanding the aging, xenophobic despot afresh. With the benefit of new research and information, both historical and medical, this book demonstrates that his psychology and a horrific litany of ailments and disorders were major contributory factors to his decisions and actions.

This an account of the epic tragedy of Henry’s last seven turbulent years, as the vultures of disease roosted around him and he fought and lost his last battle against geriatric decay, becoming ever more irrational and dangerous even to those close to him, or whom he loved.

As he lay dying, his doctors were too afraid to warn him of his impending demise. Predicting the king’s death was a capital offence under his own draconian treason laws

Book Details:

- Author: Robert Hutchinson

- On Submission

-

Rights Sold

- UK: Weidenfeld

Robert Hutchinson

Robert Hutchinson, author and broadcaster started his working life as a reporter on regional newspapers before joining The Press Association, (the news agency for UK and Irish media) as a night sub-editor. He returned to reporting, later becoming Defence Correspondent. In late 1983 he joined Jane’s Publishing Company as one of the team that successfully launched Jane’s Defence Weekly and became Publishing Director of Jane’s Information Group in 1987, responsible for its magazines, newsletters, books and digital products.Leaving a decade later, he compiled and edited two ed...

More about Robert Hutchinson